Kandy Hidden away amid precipitous green hills at the heart of the island, KANDY is Sri Lanka’s second city and undisputed cultural capital of the island, home to the Temple of the Tooth, the country’s most important religious shrine, and the EsalaPerahera, its most exuberant festival. The last independent bastion of the Sinhalese, the Kingdom of Kandy clung onto its freedom long after the rest of the island had fallen to the Portuguese and Dutch, preserving its own customs and culture which live on today in its unique music, dance and architecture. The city maintains a somewhat aristocratic air, with its graceful old Kandyan and colonial buildings, scenic highland setting and pleasantly temperate climate. And although modern Kandy has begun to sprawl considerably, the twisted topography of the surrounding hills and the lake at its centre ensure that the city hasn’t yet overwhelmed its scenic setting, and it preserves at its heart a modest grid of narrow, low-rise streets which, despite the crowds of people and traffic, retains a surprisingly small-town atmosphere.

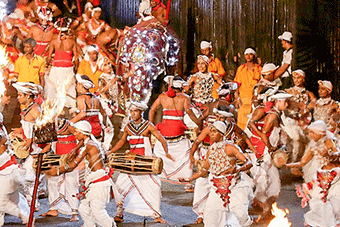

Brief history Kandy owes its existence to its remote and easily defensible location amid the steep, jungle-swathed hills at the centre of the island. The origins of the city date back to the early thirteenth century, during the period following the collapse of Polonnaruwa, when the Sinhalese people drifted gradually southwards (sec p.402). During this migration, a short-lived capital was established at Gampola, just south of Kandy, before the ruling dynasty moved on to Kottc, near present-day Colombo. A few nobles left behind in Gampola soon asserted their independence, and subsequently moved their base to the still more remote and easily defensible town of Senkadagala during the reign of Wickramabahu III of Gampola (r. 1357-74). Senkadagala subsequently became known by the sweet-sounding name of Kandy, after Kanda UdaPasrata, the Sinhalese name for the mountainous district in which it lay (although from the eighteenth century, the Sinhalese often referred to the city as MahaNuwara, the “Great City”, a name by which it’s still sometimes known today). The rise of the Kandyan kingdom By the time the Portuguese arrived in Sri Lanka in 1505, Kandy had established itself as the capital of one of the island’s three main kingdoms (along with Kottc and Jaffna) under the rule of SenaSammathaWickramabahu (r. 1473-151 1), a member of the Kotte royal family who ruled Kandy as a semi-independent state. The Portuguese swiftly turned their attentions to Kandy, though their first expedition against the city ended in failure when the puppet ruler they placed on the throne was ousted by the formidable Vimala Dharma Suriya, the first of many Kandyan rulers who tenaciously resisted the European invaders. As the remainder of the island fell to the Portuguese (and subsequently the Dutch), the Kandyan kingdom clung stubbornly to its independence, remaining a secretive and inward-looking place, protected by its own inaccessibility — Kandyan kings repeatedly issued orders prohibiting the construction of bridges or the widening of footpaths into the city, fearing that they would become conduits for foreign attack. The city was repeatedly besieged and captured by the Portuguese (in 1594, 1611, 1629 and 1638) and the Dutch (in 1765), but each time the Kandyans foiled their attackers by burning the city to the ground and retreating into the surrounding forests, from where they continued to harry the invaders until THEESALAPERAHERA Kandy's ten-day EsalaPerahera is the most spectacular of Sri Lanka's festivals, and one of the most colourful religious pageants in Asia. Its origins date back to the arrival of the Tooth Relic (see box, p.212) in Sri Lanka in the fourth century AD, during the reign of KirtiSiriMeghawanna, who decreed that the relic be carried in procession through the city once a year. This quickly developed into a major religious event - the famous Chinese Buddhist Fa-Hsien, visiting Anuradhapura in 399 AD, described what had already become a splendid festival, with processions of jewel-encrusted elephants. Occasional literary and artistic references suggest that these celebrations continued in some form throughout the thousand years of upheaval which followed the collapse of Anuradhapura and the Tooth Relic's peripatetic journey around the island. Esala processions continued into the Kandyan era in the seventeenth century, though the Tooth Relic lost its place in the procession, which evolved into a series of lavish parades in honour of the city's four principal deities: Vishnu, Kataragama, Natha and Pattini, each of whom had (and still has) a temple in the city. The festival took shape in 1775, during the reign of Kirti Sri Rajasinha, when a group of visiting Thai clerics expressed their displeasure at the lack of reverence accorded to the Buddha during the parades.To propitiate them, the king ordered theTooth Relic to be carried through the city at the head of the four temple processions: a pattern that endures to this day. Sri Rajasinha's own enthusiastic participation in the festivities, and that of his successors, also added a political dimension - the Nayyakar kings of Kandy (who were from South India) probably encouraged the festival in the belief that by associating themselves with one of Buddhism's most sacred relics, they would reinforce their dynasty's shaky legitimacy in the eyes of their Sinhalese subjects.TheTooth Relic itself was last carried in procession in 1848, since when it's been considered unpropitious for it to leave the temple sanctuary - its place is now taken by a replica. THE FESTIVAL The ten days of the festival begin with the Kap Tree Planting Ceremony, during which cuttings from a tree - traditionally an Esala tree, though nowadays a Jak or Rukkattana are more usually employed - are planted in the four devales (see p.217), representing a vow [kap) that the festival will be held. The procession (perahera) through the streets of Kandy is held nightly throughout the festival: the first five nights, the so-called KumbalPerahera, are relatively low-key; during the final five nights, the RandoliPerahera, things become progressively more spectacular, building up to the last night, the MahaPerahera, or'Great Parade", featuring a massive cast of participants including as many as a hundred brilliantly caparisoned elephants and thousands of drummers, dancers and acrobats walking on stilts, cracking whips, swinging fire pots and carrying banners, while the replica casket of theTooth Relic itself is carried on the back of the Maligawa Tusker elephant (see p.215). Following the last perahera, the water-cutting ceremony is held before the dawn of the next day at a venue near Kandy, during which a priest wades out into the Mahaweli Ganga and'cuts' the waters with a sword.This ceremony symbolically releases a supply of water for the coming year (theTooth Relic is traditionally believed to protect against drought) and divides the pure from the impure - it might also relate to the exploits of the early Sri Lankan king, Gajabahu (reigned 114-136 AD), who is credited with the Moses-like feat of dividing the waters between Sri Lanka and India in order to march his army across during his campaign against the Cholas. they were forced to withdraw to the coast. Despite its isolation, the kingdom’s prestige as the final bastion of Sinhalese independence was further enhanced during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by the presence of the Tooth Relic (see box, p.212), the traditional symbol of Sinhalese sovereignty, while an imposing temple, the Temple of the Tooth, was constructed to house the relic. The Nayakkar dynasty It had long been the tradition for the kings of Kandy to take South Indian brides descended from the great Vijayanagaran dynast)1, and when the last Sinhalese king of Kandy, Narendrasinha, died in 1739 without an heir, the crown passed to his Indian After the water-cutting ceremony, at 3pm on the same day, there's a final “day’' perahera (DawalPerahera), a slightly scaled-down version of the full perahera. It's not as spectacular as the real thing, though it does offer excellent photo opportunities. THE PROCESSION The perahera is a carefully orchestrated, quasi-theatrical event - there is no spectator participation here, although the astonishing number of performers during later nights give the impression that most of Kandy's citizens are involved. The perahera actually comprises five separate processions, which follow one another around the city streets: one from the Temple of the Tooth, and one from each of the four devales - a kind of giant religious conga, with elephants. The exact route changes from day to day, although the procession from the Temple of the Tooth always leads the way, followed (in unchanging order) by the processions from the Natha, Vishnu, Kataragama and Pattinidevales (Natha, as a Buddha-to-be, takes precedence over the other divinities). As its centrepiece, each procession has an elephant carrying the insignia of the relevant temple - or, in the case of the Temple of the Tooth, the replica Tooth Relic. Each is accompanied by other elephants, various dignitaries dressed in traditional Kandyan costume and myriad dancers and drummers, who fill the streets with an extraordinary barrage of noise. The processions each follow a broadly similar pattern, although there are slight differences.TheKataragama procession - as befits that rather unruly god - tends to be the wildest and most free-form, with jazzy trumpet playing and dozens of whirling dancers carrying kavadis, the hooped wooden contrivances, studded with peacock feathers, which are one of that god's symbols. The Pattini procession, the only one devoted to a female deity, attracts mainly female dancers. The beginning and end of each perahera is signalled by a deafening cannon shot. PERAHERA PRACTICALITIES The perahera is traditionally held over the last nine days of the lunar month of Esala, finishing on NikiniPoya day - this usually falls during late July and early August, though exact dates vary according to the vagaries of the lunar calendar. Dates can be checked on Osridaladamaligawa.lk and Odaladamaligawa.org. Accommodation during the EsalaPerahera can get booked up months in advance, and prices in most places double or triple - be sure to reserve as far in advance as possible. The perahera itself begins between 8pm and 9pm. You can see the parade for free by grabbing a spot on the pavement next to the route. During the early days of the perahera it's relatively easy to find pavement space; during the last few nights, however, you'll have to arrive four or five hours in advance and then sit in your place without budging - even if you leave for just a minute to go to the toilet, you probably won't get your spot back. Not surprisingly, most foreigners opt to pay to reserve one of the thousands of seats which are set out in the windows and balconies of buildings all along the route of the perahera. On the last three or four nights seats start at $20 for the cheapest spots (usually on the upper floors of streetside buildings and with restricted views) and go for $50 or more for good street-level positions with unrestricted views - while the very best seats can go for considerably more than this; on earlier nights a good seat will cost $25-35. If possible, check exactly which seat you're being offered before handing over any cash, and beware of unscrupulous touts who might simply disappear with your money - it's safest to book a seat through your guesthouse or hotel. The three-temples loop The countryside around Kandy is dotted with dozens of historic Kandyan-era temples, most of them still largely unvisited by foreign visitors. The most interesting are the Embekke, Lankatilake and Gadaladeniya, which lie some 10km west of Kandy and make for a rewarding half-day walk (see box opposite) popularly known as the three-temples loop; they can be visited rather more quickly but less memorably by car or tuktuk. All three temples were constructed during the fourteenth century, in the early days of the nascent Kandyan kingdom, when the region was ruled from Gampola and Tamil influence was strong. There's a further trio of temples to the east of Kandy (see p.231). EmbekkeDevale Daily 8am-6pm • Rs.300 • Buses to Embekke depart from the Clocktower bus station (every 30min; 1hr) Dating from the fourteenth century, the rustic little EmbekkeDevale, dedicated to Kataragama, is famous principally for the fine pavilion, the digge (drummers pavilion), fronting the main shrine. The digges intricately decorated wooden pillars were apparently brought here from another temple at Gampola; each bears a different design, with an entertaining jumble of peacocks, entwined swans, wrestlers, dragons, dancers, horsemen, soldiers and bodhisattvas (shown as composite figures: half man, half bird). One of the most famous panels depicts an elephant and lion fighting; another shows what looks curiously like a Habsburg double-headed eagle. Two quaint lions flank the entrance to the main shrine behind, topped by a delicate tower. To the left of the main building stands a rustic granary (signed “Ancient Paddy Barn”) raised on stones above the ground to protect its contents from wild animals. Lankatilake Daily 8am-6pm • Rs.300 • Buses to Lankatilake depart from the Goods Shed bus station (every 30min; 1 hr) Built on a huge rock outcrop, the imposing Lankatilake is perhaps the finest temple in the district. Founded in 1344, its architecture is reminiscent of the solid, gedige-style stone temples of Polonnaruwa rather than the later and more decorative Kandyan-style wooden temples. The building was formerly four storeys tall, though the uppermost storeyscollapsed in the nineteenth century and were replaced by the present, badly fitting wooden roof. The gloomy central shrine, with eighteenth-century Kandyan paintings, is magically atmospheric: narrow but tall, and filled with a great seated Buddha under a huge makaratorana, with tiers of gods rising above. The massive exterior walls contain a sequence of small shrines containing statues of Saman, Kataragama, Vishnu and Vibhishana (often kept locked, sadly), punctuated by majestic WALKING THE THREE-TEMPLES LOOP Embekke, Lankatilake and Gadaladeniya temples can all be visited (albeit with some difficulty) by bus or, far more conveniently, by taxi (count on around Rs.3000 for the round trip).The best way to visit, however, is to walk at least part of the way between the three, starting at the EmbekkeDevale and finishing at the Gadaladeniya (or vice versa). To reach the EmbekkeDevale and the start of the walk, take bus #643 from the Goods Shed bus station (every 30min; 1 hr) - the bus tends to leave from the left-hand side of the station in front of the row of shops rather than from one of the actual bus stands. All being well you'll be dropped off on the main road through Embekke village, from where a black sign points down a side road to the EmbekkeDevale. Walk down this road for 800m then turn right and you'll see the EmbekkeDevale directly in front of you. Continue along the road past the EmbekkeDevale. Go left at the T-junction, which now begins to climb steeply about 200m further on, and continue climbing for another 750m until you reach the edge of the village, marked by a gorgeous bo tree and paddy fields. Continue straight on for a further 500m until the road forks. Keep right and continue over the brow of a hill and down the other side. You'll now catch your first glimpse of the Lankatilake, almost obscured by trees on the steep little hillock ahead on your left. Turn left down the short road next to a line of small pylons to reach the base of the hill, from where a magnificent flight of ancient rock-cut steps (alongside a less treacherous set of modern stone steps) leads precipitously up to the temple itself. From the Lankatilake temple, return to the road by the pylons and go left, walking uphill (again) to reach a larger road and a few shops. Turn left again and follow this road for about 1 km to reach the village of Pamunuwa and then continue another 2km to reach the Gadaladeniya temple (next to the road on the left). This part of the walk is less special - the road is bigger, there's more traffic and you might prefer to just jump into a tuktuk to reach Gadaladeniya. The area is also a major metalworking centre, and you’ll pass dozens of shops selling traditional oil lamps, looking a bit like overblown cake stands. Beyond Gadaladeniya, carry on along the road for a further ten to fifteen minutes past numerous metalworking shops to reach the busy town of Pilimathalawa on the main Colombo-Kandy highway. Turn right along the highway and walk through town for about 200m and you'll find a bus stop in front of Cargills and the Commercial Bank. Buses back to Kandy pass every minute or so - just flag one down.